The UN International Resource Panel recently launched a report on ‘Mineral Resources Governance in the 21st Century – Gearing Extractive Industries Towards Sustainable Development’. During a short webinar the international framework was presented and a.o. the concept of ‘Sustainable Development License to Operate’ (SDLO) was introduced. With this webinar, the high-level multi-stakeholder expert panel continued its activities towards the development of a series of policy recommendations for the EC. (Leuven, 15 July 2019)

Context

On June 6, the NEMO, CROCODILE and TARANTULA projects joined efforts to organise a clustering event on “The way forward for ‘Social License to Operate’ (SLO) in Europe”. Shortly after the workshop, an article summarizing the main lessons learned was published on the KU Leuven SIM² website (see: kuleuven.sim2.be/ensuring-the-slo-concept-is-adaptive-and-resilient/). These insights, combined with the feedback from the participants given through an online evaluation form, was discussed during a conference call. The debate continued by introducing the international framework and the activities of the UN International Resource Panel.

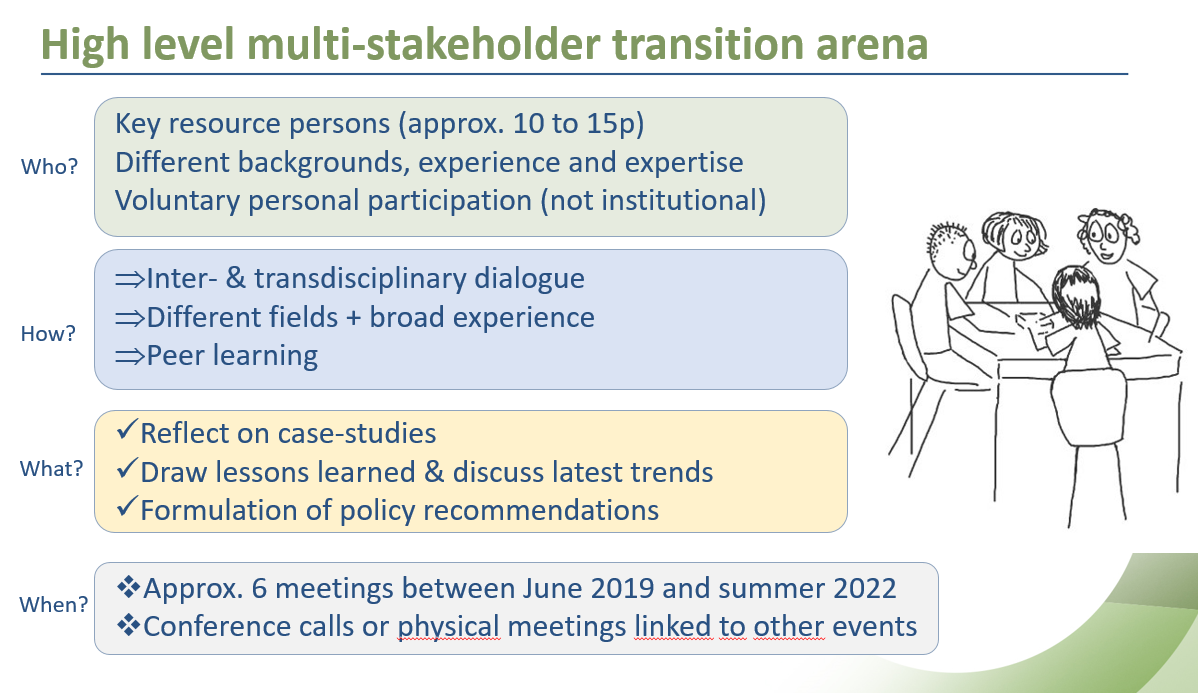

Approximately 22 participants with highly diverse backgrounds coming from academia, industry, government and civil society reflected on the lessons learned and the challenges ahead. With this webinar, the high-level multi-stakeholder expert panel continued its activities towards the development of a series of policy recommendations for the EC.

Social License to Operate in H2020 projects

The NEMO, CROCODILE and TARANTULA projects aim to enhance resource recovery from primary and secondary streams. By applying innovative technologies, NEMO intends to recycle waste from mine tailings; CROCODILE focuses on the recovery of cobalt from primary sources (e.g. laterite ores) and secondary waste streams (e.g. end-of-life batteries); TARANTULA aims to recover refractory metals Tungsten, Niobium and Tantalum from mining waste and process scrap.

NEMO, CROCODILE and TARANTULA are three H2020 projects which focus on resource recovery.

All three projects combine these technological innovations with a strong stakeholder involvement. They plan to implement an enhanced dialogue framework between industry, government, academia and civil society in order to obtain and maintain the ‘Social License to Operate’ (SLO). In order to do so, they propose the combination of a ‘bottom-up’ and ‘top down’ approach: i) support bottom-up meetings with local residents living in the vicinity of the operations and discuss the barriers and opportunities for the implementation of the new technologies; ii) host a ‘high-level multi-stakeholder expert panel’ to reflect on the various case studies, formulate lessons learned, and develop policy recommendations. The webinar is part of this ‘top down’ strategy.

The high level multi-stakeholder expert panel discusses o.a. latest trends of research on the 'Social License to Operate' concept

Debating Social License to Operate

On June 6, the NEMO, CROCODILE and TARANTULA projects joined efforts to organise a clustering event on “The way forward for ‘Social License to Operate’ (SLO) in Europe”. The workshop was evaluated positively. An inter- and transdisciplinary audience actively exchanged visions. However, it was questioned whether we only reach the supporters of the SLO-concept.

Four main lessons learned were drawn from the MIREU-workshop and described in an article on KU Leuven SIM² website[1]:

- Link production processes and end product

- Distinguish between end product and production processes

- SLO reflects a long term relationship

- There is no European policy on SLO yet

Several participants provided their feedback shortly after the workshop and highlighted the following key issues:

- SLO is an ongoing process which requires a proactive involvement of citizens to build a strong relationship. There are conceptual differences from SLO and the official planning/ participatory processes needed to pass an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA).

- Mainstreaming SLO requires a combination of a top down political commitment and a bottom up push to enhance the process.

- A value based approach rather than a stakeholder approach is relevant to identify relevant actors; this is applied in the MIREU model on SLO.

- SLO is very context dependent and differs from region to region; Europe needs to find its own way of adopting and understanding SLO.

- There is a lack of consensus around SLO because “the jelly has yet to be nailed to the wall”. The visions from industry and NGOs differ largely (e.g. can/should SLO be regulated or not).

- The desire for mineral extraction pushes many to believe in a utopian technological world. SLO is vulnerable to (ab)use to continue mining activities.

After the presentation of the above, the following issues are reflected upon by the webinar participants:

- SLO reflects an intangible long term relationship, and therefore is difficult to regulate. Regulators should not ignore SLO, but take it into account, give it a higher importance and monitor the SLO related activities.

- Distinction must be made between the role of the policy maker versus regulator. With respect to SLO, policy makers can promote dialogue through regulation. Regulations can protect (participatory) processes and allow for monitoring of SLO.

- Companies and local actors are sometimes well ahead of the regulations and are already implementing SLO related activities in the field. The private sector generally regards SLO as descriptive of a positive relationship between a company and its various stakeholders, but considers that it should not become prescriptive.

Introducing the international framework: Mineral Resources Governance in the 21st Century – key facts and messages.

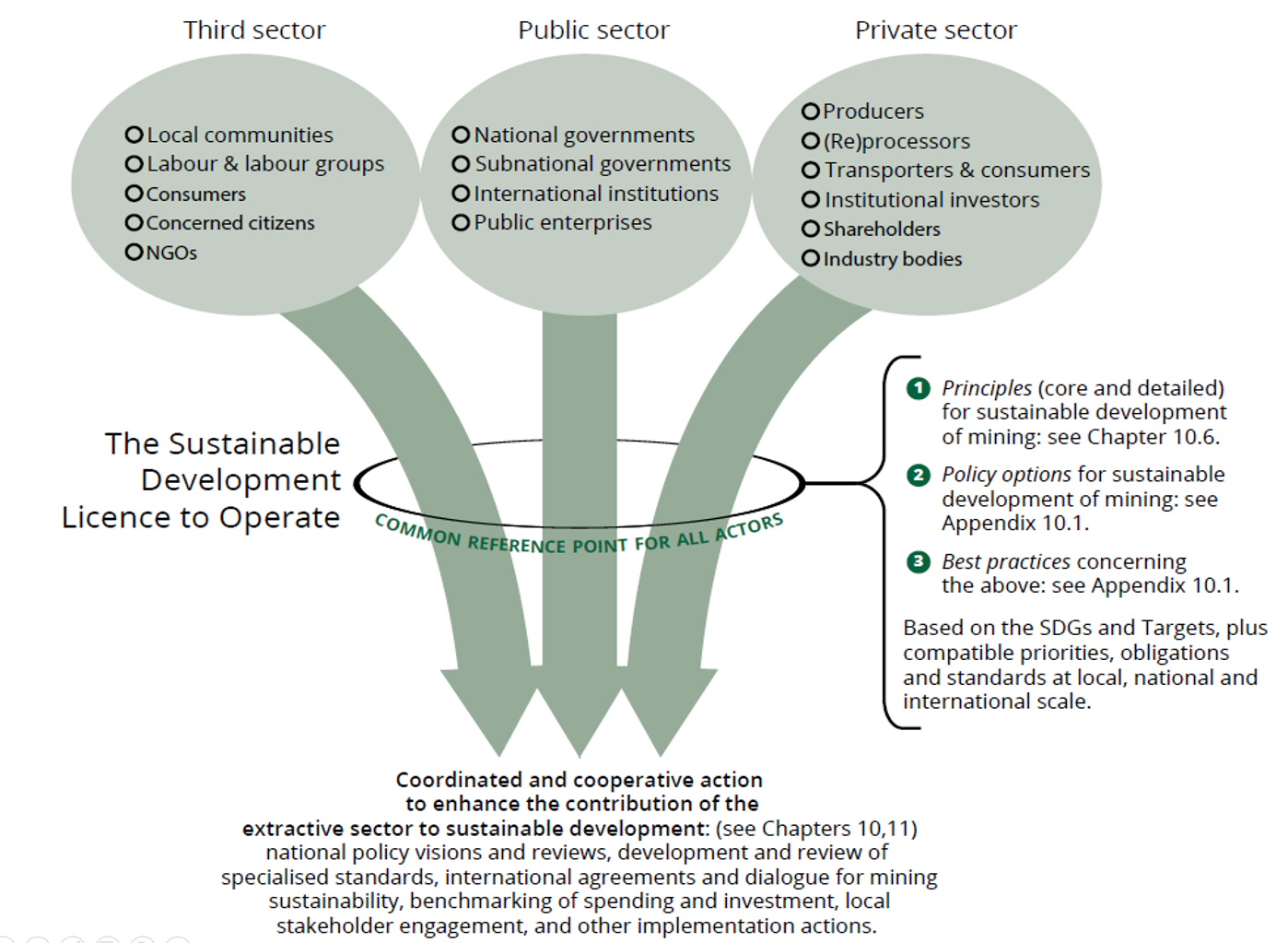

In his presentation (see download below), Antonio Pedro presents an overview of (i) the key challenges for the governance of mineral resources, (ii) a new governance framework: the ‘Sustainable Development License to Operate’ (SDLO), and (iii) the practical implications of SDLO and the next steps.

The extractive industries could struggle to meet the demand over the next 2-3 decades. Many developing countries will require many resources to ensure a higher wellbeing of its citizens (e.g. infrastructure, housing). The transition to a low-carbon economy is also highly resource intensive. If well managed and governed, the extractive sector has a large potential to contribute to the achievement of the SDGs. The SLO continues to be a major concern in industry, as reflected in the Ernest Young 2019-2020 10 Top Business Risks in the extractive industry.

There are many governance challenges in extractive industries (e.g. enclaved nature, negative and enduring impacts of mining, lack of accountability and transparency, etc.). In several cases, billions of dollars of investment are stalled because of different perceptions of what constitutes value. The concept of SDLO addresses these differing visions and can lead to a shared understanding of what constitutes value. There are various levels of shared value creation: from fair revenue sharing between companies and governments, to enhancing intergenerational equity, mining responsibly, reducing the energy intensity of production processes, deepening value chains in producing countries, fostering the circular economy, respecting human rights, eliminating child labour, securing access to resources, satisfying consumer demands as well as creating an enabling local environment and sustaining livelihoods beyond the closure of mining.

The SDG agenda induces a paradigm shift towards a more holistic outcome, recognizing our planetary boundaries. The sector-specific and fragmented nature of current mining governance practices is incompatible with this holistic decision-making. The SLO approach does not accommodate the nexus of environmental, social and economic concerns at multiple levels of social, temporal, intergenerational and spatial scales. A new flexible framework is proposed which builds further on and extends the SLO concept: the ‘Sustainable Development License to Operate’ (SDLO).

The Sustainable Development License to Operate concept addresses the nexus of environmental, social and economic concerns at multiple levels and scales

The International Resource Panel drafted a report “Mineral Resource Governance in the 21st Century – Gearing Extractive Industries Towards Sustainable Development”. The full report will be published in the coming weeks; a summary for policy makers and a press release are already available[2]. The report includes a.o. the proposed SDLO framework (see Figure 1), and describes the various challenges and practical implications towards developing an integrated resource governance framework.

The authors of the above mentioned report suggest to further develop global international agreements and to create an International Resource Agency (similar to the International Energy Agency) which focuses on the mainstreaming of sustainable development across mining value chains. They noted that advancing governance in the extractive sector is a joint responsibility of several stakeholders both in host and home countries and would require multiple actions in several fronts. The dialogue on the several cross-cutting issues illuminated by the SDLO concept should be continued at a Global Platform (e.g. G20). Complementary to these, regional platforms and national level initiatives should promote the realisation of the SDG agenda. Finally, a series of initiatives which aim to improve the performance of the extractive sector are listed. Consolidation of these major governance initiatives would facilitate their understanding, uptake, internalisation and incorporation of its key guiding principles in relevant policy instruments and business models.

The Resolution 4-19 of the UN Environment Assembly (UNEA 4) on Mineral Resource Governance calls for knowledge sharing, collection of best practices, promotion of eco-innovation, advancement of sustainability in sand mining and the development, implementation and dissemination of an industry tailings dam standard. The challenge is now how to operationalise of these recommendations. The Brumadinho tailings dam disaster indicates how urgent these tasks are.

Out of the UNEA 4, the member countries requested the UN to look into the governance issue of the mining sector. The work of the IRP, and the work on mine tailings and sand mining, will constitute an input to UNEA 5 which will take place end of February 2021. The UN IRP aims at fostering a science based dialogue with policy makers, industry and the NGO community, so that an informed policy debate is conducted before going into UNEA 5. Based on this input, a recommendation will be formulated by the Assembly. The goal for the IRP is to ensure that science is informing policy, and to take the dialogue as widely as possible. The input documents for UNEA should be ready by end of 2020.

After the presentation, some questions were raised and comments given:

- The report criticizes the multitude of existing governance schemes, but recognizes the importance of these ongoing processes. The suggestions from the report are intended to further push this agenda forward. In the revision of the various processes, the SDLO framework can be considered.

- The various existing schemes are sometimes confusing. Some schemes are being implemented in some countries but unknown in others. Increased transparency through e.g. a mapping on which sites claim to be managed ethically and responsibly, could complement the paper based reporting.

- Sustainability is included in the current SLO concept; the SDLO concept makes this more explicit.

- Given the nature of mining as a temporal and non-renewable activity with current issues on transparency, accountability and social distrust, it is questioned whether the achievement of the SDGs and the implementation of a holistic mining industry vision is possible within the current legislation framework. As confirmed by the OECD, the existing contracts and legislation often have limitations. As part of the UN SDG Solutions Network, a team on good governance of extractive resources is advocating to move from negotiation to regulating the extractive operations to reduce the discretionary powers of the government and other actors, and to include the key principles embodied in legislation. This could a.o. reduce the issue of e.g. information asymmetry.

- If managed well, the extractive industry sector could contribute to sustainable development, reducing poverty, transition to a carbon-neutral world, etc.. but this requires major improvements in its governance.

- A strong partnership between government, private sector, civil society and local communities is needed to develop a SDLO in which all kind of stakeholders define what constitutes a shared value, contribute to decision-making and benefit fairly from the proceeds of mining.

Next steps

During the coming months the exchange will continue via e-mail; another conference call will be organised during the second half of September. The next meeting of the high-level multi-stakeholder expert panel is foreseen for November 2019. From 18 to 22 November 2019, the EU Raw Materials Week is organised in Brussels; on Thursday November 21, a session will be dedicated to “Raw Materials meeting societal needs” in which the topic of SLO can be further debated. Several side events are also being organised. For more information, contact Piet Wostyn.

Download here the presentation of Antonio Pedro on the UN International Resource Panel report.